By Paula Ratliff

PEARL HARBOR, Hawaii—Thousands of people gathered here on Tuesday to commemorate the 80th Anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The surprise assault by the Imperial Japanese Navy on Dec. 7, 1941, carried out prior to a declaration of war, plunged the United States into World War II.

The ceremony honored the fallen, encouraged the survivors, and brought healing and closure to the 396 families who waited for their loved ones to finally be identified. A smaller group of families, 33 in all, re-interred the remains of fallen warriors who have remained unidentified despite years of effort.

The Japanese arrived quietly on a Sunday morning with dive bombers, torpedoes, and suicide planes, raining terror throughout the Island. One wave came, then a second, killing 2,402 people and wounding 1,143.

Amidst of chaos, acts of valor, bravery, and sacrifice quelled the destruction of war. The survivors witnessing the fury in the skies sprang into action, fighting back until the last plane was no longer a threat. Twenty–nine planes and five submarines were destroyed.

Lewis Walters, who was 16 at the time, and his father, George Walters worked in the Navy yard at Pearl Harbor. Walters recalled that his father did not have a weapon, but he used his crane to protect the USS Pennsylvania, keeping it in the path of incoming bombers and using the boom as a pointer to warn gunners of approaching planes.

Lewis was home when he heard the announcement over the speakers, “This is not an exercise. This is the real thing. All shipyard workers report to the Navy yard.” He “zigzagged” trying to dodge the bullets; yet, his truck was damaged, spilling out into the road. “I used pieces of it as a shield, as I ran toward the port, dodging bullets as I ran” he told reporters at Pearl Harbor.

When he arrived, he was instructed to help gather bodies and take them to a makeshift morgue. He recalled spending many days working around the clock to make repairs on the ships.

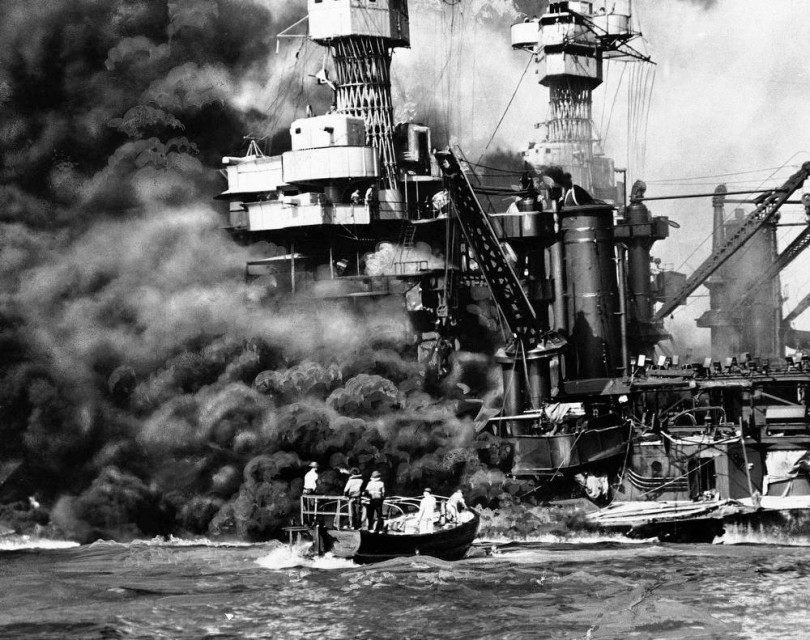

Eight battleships were docked on “Battleship Row” sitting side-by-side as large floating targets, unmanned and defenseless. As the bombs detonated, the ships became infernos with ammunition exploding and burning oil leaking from the vessels. It became a race against time.

As the orders were given to “abandon ship,” some jumped, only to be engulfed in six inches of burning oil that covered the water. Some could not swim and others were injured from the jump. Some escaped the burning ships, only to be engulfed by burning debris they could not escape.

Blood floated. Heads bobbed. The rescue boats could not get close enough. Cries for help eventually became silent. The blue waters turned black.

Fires and explosions continued for days making rescue missions nearly impossible. As each ship was stabilized, the survivors removed the remains of their comrades and dive teams searched the black waters.

The majority of the US causalities were on the USS Arizona which was hit by several bombs nearly ripping the ship in half. The ship exploded and sank within 9 minutes with 1,177 members on board, leaving 1,102 trapped on the ship and only 75 making it out safely. There were approximately 260 others assigned to the ship, but they were not on board at the time of the attack.

The USS Arizona remains where it sank and is the base for the USS Arizona Memorial which is visited by over 1.8 million people each year. Since the attack, 44 survivors have chosen to be interred with their shipmates.

The USS Oklahoma suffered the second-highest number of causalities being struck with nine torpedoes. Within 15 minutes, the mighty dreadnought, measuring 583 feet and weighing over 27,500 tons, sank and capsized, trapping 429 crew members beneath the hull.

It took several months before she was eventually raised and the remains removed. In various stages of decomposition, the remains were buried in mass graves and moved several times throughout the eight decades after the attack.

The USS Utah was hit by numerous torpedoes at the beginning of the attack, quickly capsizing and sinking with 58 crew members on board. It remains submerged where it sank and for the 80th Anniversary, dive teams provided a live-stream tour of the ship, giving a glimpse into history.

Some of the battered ships sailed again eventually reaching the final battle on the Island of Okinawa. And the American troops rallied from Dec. 7, the Day of Infamy, to the Battle of Midway six months after the attack.

The large number of casualties created numerous challenges for proper identification and burial, resulting in many bodies being buried in mass graves while others remained buried at sea, some were encapsulated in their ship and others were never found.

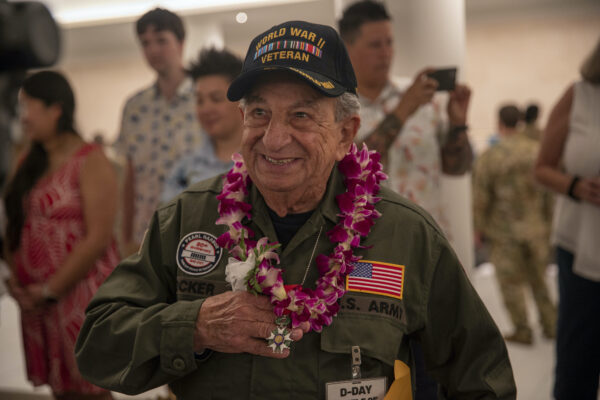

Only 32 Pearl Harbor Veterans were able to attend the anniversary this year with two from the USS Oklahoma, one from the USS Pennsylvania, and one from the USS St. Louis: a reminder that history is transitioning as these heroes are entering their late 90’s and 100’s.

Pearl Harbor survivor Ike Schab is 101 years old and was able to make the journey for this year’s anniversary. In 1941, he was a musician in the U.S. Navy and assigned to the USS Dobbin which was dry-docked at the time of the attack. On Sunday of this week, he guest-conducted the Pacific Fleet Band with the vitality of a young sailor heading out on a Saturday date.

The 80th anniversary marks the completion of a significant project to identify the remains of the fallen. The USS Oklahoma Identification Project used a variety of identification efforts, including historical and modern, to identify 396 of the 429 crew members who perished during the attack.

Kelly McKeague, Director of the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, called the anniversary a “truly a momentous occasion.”

“To say it is a milestone is not an understatement. It was the right thing to do, to provide answers to the families about their loved ones who made the ultimate sacrifice.”

In the last 80 years, the “unknowns” from the USS Oklahoma have been disinterred three times in the quest to confirm their identities. In 1947-49, the remains were disinterred from the Hawaiian Nu’uanu and Halawa cemeteries and taken to Schofield Barracks for identification efforts. Due to limited scientific methods at that time, only 35 were identified.

In 1950, the disinterred remains were buried in 62 caskets in 45 graves at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific (NMCP), commonly referred to as the Punchbowl, as their fourth place of burial.

In 2003, the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command (JPAC) disinterred a single casket, thought to contain the remains of five individuals; however, upon further scientific analysis, it was determined that it contained the remains of almost 100 crew members. From 2008-2010, five identifications were made from these remains, not having sufficient DNA from family members on file for comparison.

In 2010, Congress expanded the DPAA’s mission to include identifying the remains from WWII, noting it was unacceptable to leave our military members’ comingled bodies in mass graves.

Five years later, the 61 remaining caskets were disinterred from the Punchbowl, disturbing the graves for the fifth time.

The quest began with new technology and a new commitment to identify each member. DNA was solicited from maternal and paternal family members. Researchers then conducted an array of testing modalities including anthropology, odontology, DNA sampling, material evidence and radiograph comparisons.

The Pentagon prepared an extensive report for each member, identifying every specimen that was analyzed and included a summary of the anthropological analysis and dental records.

“They took every precaution to preserve the remains, being they were in various stages of decomposition,” Carrie LeGarde, the lead for the identification project, said.

The reports were provided to the next of kin allowing families to make the final choices regarding burial, the type of service, and the selection of a marker and casket. Once decided, the Navy Casualty Offices handled the logistics and military honors for each ceremony.

The phone calls to the families resurrected stories that had never been told. The soldiers were no longer missing in action or unidentified, they were coming home as identified American heroes.

“Even though it had been almost 80 years, it is still difficult to make the final decisions and the grieving process starts all over again,” said Betty Magers, from Smiths Grove, Kentucky.

Her brother-in-law, Howard Scott Magers was killed on the USS Oklahoma and was identified in December 2019. “He left here as a young man of 17, leaving a legacy that was filled with honor and kindness: many remembrances before the war.”

“Hundreds of people attended a graveside service to honor him. It was truly humbling and appreciated so much by the family,” she told the Epoch Times.

Welborn Lee Ashby served on the USS West Virginia and was interred on May 30, 2021, in his hometown of Centertown, Kentucky.

“When the call came, I initially thought it was a prank or someone trying to get my identity. The emotions started when I knew the call was legitimate” Ashby’s niece, Paula Kern, told The Epoch Times.

“I was thrilled that they had identified him, yet sad because his parents and sister were no longer living to celebrate his homecoming. My family knew nothing of his whereabouts all of this time. His mother had always longed to go to Hawaii to be able to just put her feet in the water where he went down, but she never lived to see that day,” Kern added.

“However, his sister would eventually travel to Hawaii in the late 1990s and was finally able to fulfill their Mother’s wish when she waded into the waters surrounding Pearl Harbor,” she continued.

“When Welborn came home, the streets were lined with people and flags. It was truly an amazing homecoming and we were so proud to honor him and all who served.”

In Akeley, Minnesota, Neal Kenneth Todd was laid to rest on July 10, 2021. His nephew, Alfred Straffenhagen III, began planning his homecoming several months in advance.

“I want him to have the homecoming he deserved” and he worked tirelessly, planning the details for the funeral mass, designating three sets of pallbearers, arranging for a horse-drawn carriage that was last used for a WWI vet, securing water cannons at the airport and Patriot Guard Riders. He also had vintage aircraft at the graveside; as well as a US Air Force flyover.

“Seeing the aircraft taxi in and going through the water cannons put a realization that it was really happening. I’m not sure I can fully express the feelings of seeing Neal’s casket for the first time. It was a powerful experience,” Todd said in an email to The Epoch Times.

As each member was identified and brought to their final resting place, locals honored the return. The celebrations included flags and ribbons, songs and prayers, dedicated roads and signs, renamed buildings, the releasing of white doves, horse-drawn carriages and hearses, and more.

As the project has now concluded, 33 crew members who could not be identified despite all efforts were re-interred in a private ceremony at the Punchbowl for the fifth time. Even though it was not the answer the families had hoped for, the ceremony still offered closure.